magic.lambda

11.0.1

See the version list below for details.

dotnet add package magic.lambda --version 11.0.1

NuGet\Install-Package magic.lambda -Version 11.0.1

<PackageReference Include="magic.lambda" Version="11.0.1" />

paket add magic.lambda --version 11.0.1

#r "nuget: magic.lambda, 11.0.1"

// Install magic.lambda as a Cake Addin #addin nuget:?package=magic.lambda&version=11.0.1 // Install magic.lambda as a Cake Tool #tool nuget:?package=magic.lambda&version=11.0.1

Hyperlambda as a Turing complete programming language

magic.lambda is where you will find the "keywords" of Hyperlambda. It is what makes Hyperlambda Turing complete, and contains slots such as [for-each], [if], and [while].

Structure

Everything is a slot in Hyperlambda. This allows you to evaluate and extend its conditional operators and logical operators the same way you would evaluate or create a function in a traditional programming language. This might at first seem a bit unintuitive if you come from a traditional programming language, but has a lot of advantages, such as allowing the computer to look at the entirety of your function object as a hierarchical tree structure, parsing it as such, and executing your lambda object as an "execution tree".

For instance, in a normal programming language, the equal operator must have a left hand side (lhs), and a right hand side (rhs). In Hyperlambda this is not true, since the equal slot is the main invocation of a function, requiring two arguments, allowing you to think about it as a function. To compare this to the way a traditional programming might have implemented this, imagine the equal operator as a function, such as the following pseudo code illustrates.

equals(object lhs, object rhs)

The actual Hyperlambda code that would be the equivalent of the above pseudo code, can be found below, and this code actually executes successfully if you execute it as Hyperlambda.

eq

.:lhs

.:rhs

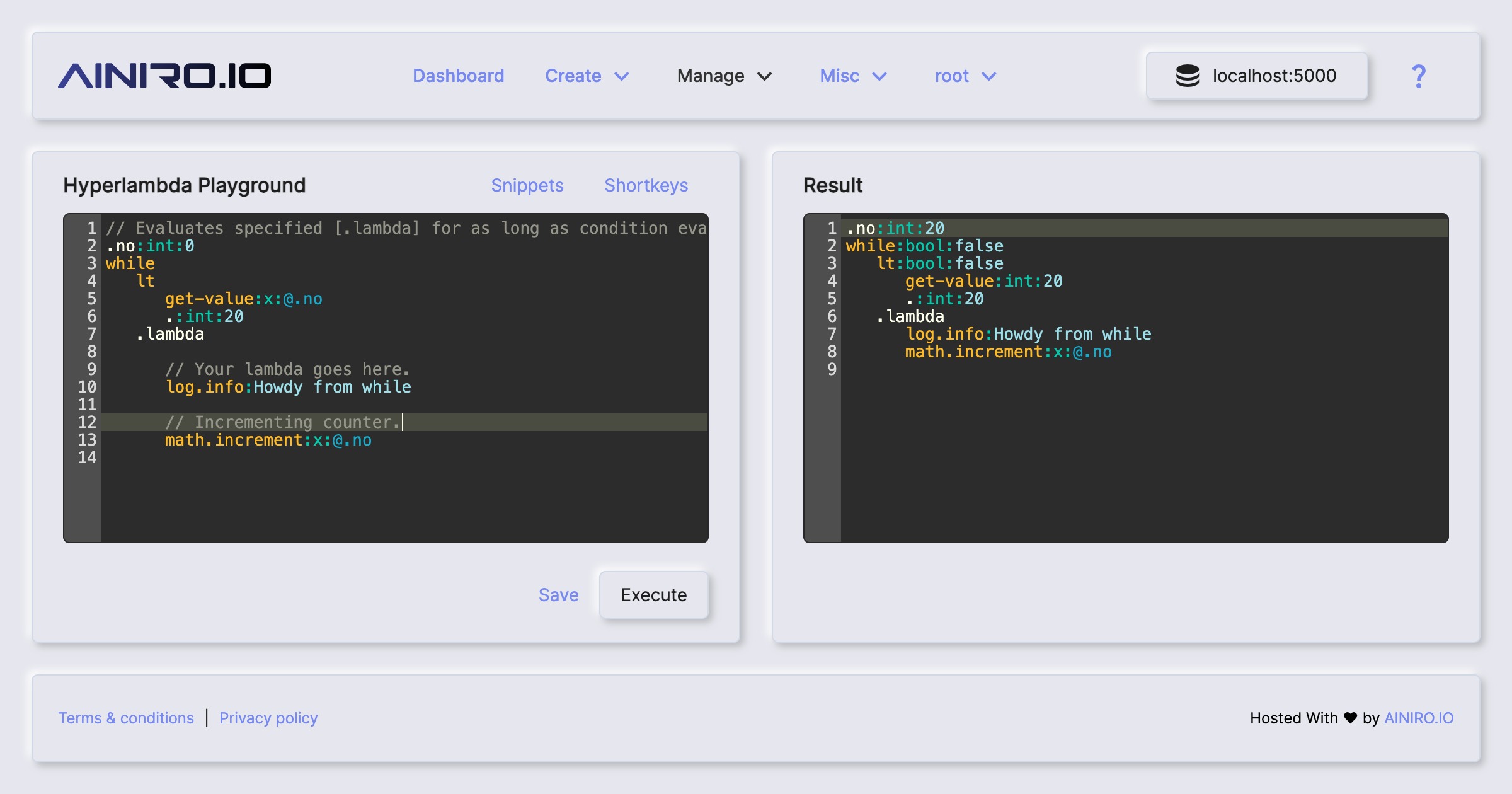

As you study Hyperlambda it might be beneficial to use the "Eval" component that you can find in its frontend dashboard. This component allows you to play with Hyperlambda in "immediate mode", experiment with Hyperlambda, execute it immediately from your browser, in a rich code editor, providing syntax highlighting for you, autocomplete on slots, etc. The "Eval" component also allows you to save your snippets for later on your server. Below is a screenshot of the "Eval" component to give you an idea of what you might expect.

If you put your cursor on an empty line and click CTRL+SPACE or FN+CONTROL+SPACE on a Mac, you will be given

autocomplete, allowing you to easily see which slots are available for you.

Logically the Hyperlambda evaluator will signal each nodes in your Hyperlambda code sequentially, assuming

all of your nodes are referencing an ISlot class, unless the node's name starts with a "." or has an empty name.

Hyperlambda structure

Hyperlambda is the textual representation of a node structure, where each node has a name, an optional value, and a collection of children nodes. Imagine the following Hyperlambda.

name:value

child1

In the above Hyperlambda there is one root node. Its name is "name", its value is "value", and this node has one child node, with the name of "child1". Its child node does not however have a value, which results in its value being "null". The reason why the Hyperlambda parser understands "child1" as the child of the "name" node, is because it is prefixed by 3 spaces (SP) relative to the "name" node. This allows you to create graph objects (tree structures) with any depth you wish, by simply starting out with the number of spaces the node above has, add 3 additional spaces, and you have declares children nodes of the node above.

If you think of these nodes as a sequence of function invocations, from the top to bottom, where all of the nodes are assumed to be referencing slots, and all children nodes arguments to your slots - You can imagine how the tree structure resulting from parsing Hyperlambda into a graph object can easily be evaluated, due to its recursive nature, making it easy to express idioms such as "if", "while", "for-each", etc. In fact logically this is similar to the way XSLT works, except there's no XML, only Hyperlambda, lambda objects, and nodes.

Since each slot will be invoked with the node referencing the slot itself as the "input" Node,

this makes the Hyperlambda evaluator recursive in nature, allowing a slot to evaluate all of its children,

after executing its custom logic, etc. And yes, before you ask, Hyperlambda has been heavily influenced by

LISP. In some ways Hyperlambda is Lisp for C#, only with a completely different syntax, and without S-Expressions.

Extending Hyperlambda

To understand the relationship between C# and Hyperlambda, it might be beneficial for you to analyze the

following code. The following code creates a new ISlot for you, implementing the interface found in

the NuGet package called "magic.signals.contracts".

using magic.node;

using magic.signals.contracts;

namespace acme.foo

{

[Slot(Name = "acme.foo")]

public class Foo : ISlot

{

public void Signal(ISignaler signaler, Node input)

{

var arg1 = input.Children.First().Get<int>();

var arg2 = input.Children.Skip(1).First().Get<int>();

input.Value = arg1 + arg2;

input.Clear();

}

}

}

The above will result in a slot you can invoke from Hyperlambda using the following code.

acme.foo

arg1:5

arg2:7

Which of course will result in the following after having been executed.

acme.foo:int:12

Notice the relationship between the [Slot(Name = "acme.foo")] C# code and the way we invoke the [acme.foo]

slot from Hyperlambda afterwards. It might help to imagine Hyperlambda as a simple string/type Dictionary,

resolving an object from your IoC container using the name of the node as the key. And in fact, this

is exactly how Hyperlambda is implemented - As a string/type dictionary, creating instances of your slot

classes using your IoC container, for then to invoke its Signal method, passing in the identity node to your slot,

where the identity node is the node invoking your signal from Hyperlambda.

To create your own C# or F# slots, you can follow the following recipe.

- Reference the NuGet package

magic.signals.contractsin your project. - Create your class, and implement the

ISlotinterface. - Mark your class with the

Slotattribute, giving it an adequateNameproperty value.

Notice - You can also implement ISlotAsync if you want to support async invocations.

The gory details

At the heart of Hyperlambda is the [eval] slot. This slot is responsible for executing your lambda object and follows a couple of simple rules. All nodes starting with a "." will be ignored, and [eval] will not try to raise these nodes as signals. This has two benefits.

- You can create "hidden" slots, that are only accessible from C#.

- You can use nodes starting with "." as data nodes, separating function invocations from data.

[eval] makes Hyperlambda "super functional" in nature. Below is an example of a Hyperlambda piece of code, that illustrates this, by adding a "callback" lambda object to its [while] invocation as a [.lambda] node, that will be invoked once for every iteration of your while loop.

.no:int:0

while

lt

get-value:x:@.no

.:int:20

.lambda

// Your lambda goes here.

log.info:Howdy from while

math.increment:x:@.no

Tokens

The separating of a node's name and its value is done by using a : character. To the left is the node's

name, and to the right is its value. The value of a node can also be a C# type of string, using double

quotes, and even single quotes, or prefix your opening double quote with an "@" character, allowing you

to use carriage returns in your strings the same way you can in for instance C#. Below are some examples.

.str1:" This is a \r\n string"

.str2:' This is also a string '

.str3:@"This

is

also a

string"

Strings in Hyperlambda can be escaped with the exact same semantics as you would escape your C# strings, including referencing UNICODE characters in your strings. Hyperlambda is always serialized using UTF8, so you can add any UNICODE characters in your Hyperlambda you wish. Just make sure you save your files as UTF8 if you are using an external code editor to edit your Hyperlambda files.

Comments

Hyperlambda accepts comments the exacts same way C# does, and you can use either multiline comments or single line comments, like the following example illustrates.

/*

* Multiline comment.

*/

// Single line comment.

You cannot put comments on lines containing nodes, and comments must be indented the same amount of indentations as the nodes they are commenting, implying the nodes below them. Below is an example.

.data

foo1:bar1

foo2:bar2

for-each:x:@.data/*

// This is correct indentation.

set-value:x:@.dp/#

.:Loop was here ...

Since Hyperlambda is using spaces (SP characters) to denote scope, indentation is important, also for comments. If you de-indent the above comment, you might get unpredictable results, in particular if you're serializing and de-serializing your Hyperlambda preserving comments. Comments should as a general rule of thumb be applied with the same amount of indentation as the node below them.

Data segments

Hyperlambda does not separate between a "variable" and a "function invocation". Hence, a node

might serve as both at the same time. This allows you to dynamically modify your lambda structure, as you

traverse it and execute it. But this creates another problem for you, which is that you will need

a mechanism to store data. This is accomplished by prefixing a node's name with a . character, at which point

the Hyperlambda evaluator will ignore it, as it is traversing your tree, and not attempt to signal

that particular node as a slot. Think of all nodes starting with a . character as "data segments",

or variables for that matter. Below is an example where [eval] will simply ignore the [.src] node

and the [.dest] node, not attempting to invoke these as slots, but treat these as "data nodes".

.src:foo

.dest

set-value:x:@.dest

get-value:x:@.src

If you change name of the above [.src] node to simply [src], your code will raise an exception, with an error such as follows "No slot exists for [src]" since this slot doesn't exist in your Hyperlambda vocabulary - Unless you for some reasons have an installation where this slot has been explicitly added to your vocabulary.

[eval]

This is the by far most important slot in Hyperlambda, since it's arguably "the heart" of Hyperlambda, allowing Hyperlambda to execute Hyperlambda. This slot executes the specified lambda object(s) assumed to exist either as a lambda in its children collection, or as an expression leading to one or more nodes, where each of these nodes will be executed. The example below illustrates how to use [eval] with an expression.

.res

.lambda

set-value:x:@.res

.:OK

eval:x:@.lambda

Notice, you could have multiple [.lambda] nodes in the above Hyperlambda, at which point all of these would be executed consecutively. Below is an example.

.res:

.lambda

set-value:x:@.res

strings.concat

get-value:x:@.res

.:" OK 1 "

.lambda

set-value:x:@.res

strings.concat

get-value:x:@.res

.:" OK 2 "

eval:x:../*/.lambda

You can also provide the lambda object as children of the [eval] node itself, such as the following illustrates.

.res

eval

set-value:x:@.res

.:Yup!

Notice, the [eval] slot is not immutable, as in it has access to the outer graph object such as illustrated above, where we set the value of a node existing outside of the [.lambda] itself. Implying [eval] cannot return values or nodes the same way for instance [signal] can.

Branching and conditional execution

Branching implies to change the execution path of your code, and examples includes function invocations, and

other similar mechanisms that changes the position of your computer's "execution pointer". Conditional

branching implies to changing the position of the execution pointer, according to some condition. Typically

this implies constructs such as if, else, goto etc in traditional programming languages.

Hyperlambda contains the following branching slots by default.

[if]

This is the Hyperlambda equivalent of if from other programming languages. It allows you to test for some condition,

and evaluate a lambda object, only if the condition evaluates to true. [if] must be given two arguments.

The first argument can be anything, including a slot invocation - But its second argument must be its [.lambda]

argument. The [.lambda] node will be evaluated as a lambda object, only if the first argument to [if] evaluates

to boolean true. Below is an example.

.dest

if

.:bool:true

.lambda

set-value:x:@.dest

.:yup!

All conditional slots, including [if], optionally accepts slots as their first condition argument. This allows you to invoke slots, treating the return value of the slot as the condition deciding whether or not the [.lambda] object should be executed or not. Below is an example.

.arguments

foo:bool:true

.dest

if

get-value:x:@.arguments/*/foo

.lambda

set-value:x:@.dest

.:yup!

Notice, both the [if] slot and the [else-if] slot can optionally be directly pointing to an expression,

that is assumed to evaluate to either boolean true or boolean false, such as the following illustrates.

.arguments

foo:bool:true

.dest

if:x:@.arguments/*/foo

set-value:x:@.dest

.:yup!

If you use this shorthand version for the slot(s), its lambda object is assumed to be the entirety of the content of the [if] or [else-if] slot itself, and there are no needs to explicitly declare your lambda objects as a [.lambda] argument. This only works if the expression leads to a boolean value.

[else-if]

[else-if] is the younger sibling of [if], and must be preceeded by its older sibling, or other [else-if] nodes, and will only be evaluated if all of its previous conditional slots evaluates to false - At which point [else-if] is allowed to test its condition - And only if its condition evaluates to true, it evaluate its lambda object. Semantically [else-if] is similar to [if], in that it requires two arguments with the same structure as [if].

.dest

if

.:bool:false

.lambda

set-value:x:@.dest

.:yup!

else-if

.:bool:true

.lambda

set-value:x:@.dest

.:yup2.0!

[else-if] can also be given an expression directly the same way [if] can. See the example for [if] to understand how this works.

[else]

[else] is the last of the "conditional siblings" that will only be evaluated as a last resort, only if none of its elder "siblings" evaluates to true. Notice, contrary to both [if] and [else-if], [else] contains its lambda object directly as children nodes, and not within a [.lambda] node. This is because [else] does not require any conditional arguments like [if] and [else-if] does. An example can be found below.

.src:int:3

.dest

if

eq

get-value:x:@.src

.:int:1

.lambda

set-value:x:@.dest

.:yup!

else-if

eq

get-value:x:@.src

.:int:2

.lambda

set-value:x:@.dest

.:yup2.0!

else

set-value:x:@.dest

.:nope

[switch]

[switch] works similarly to a switch/case block in a traditional programming language, and will find the first [case] node with a value matching the evaluated value of the [switch] node, and execute that [case] node as a lambda object.

.val:foo

.result

switch:x:@.val

case:bar

set-value:x:@.result

.:Oops

case:foo

set-value:x:@.result

.:Success!

[switch] can only contain two types of children nodes; [case] and [default]. The [default] node will be evaluated if none of the [case] node's values are matching the evaluated value of your [switch]. Try evaluating the following in your "Eval" component to understand this.

.val:fooXX

.result

switch:x:@.val

case:bar

set-value:x:@.result

.:Oops

case:foo

set-value:x:@.result

.:Oops2.0

default

set-value:x:@.result

.:Success!

In the above, the expression evaluated in the switch, which is @.val will become "fooXX" after evaluating it.

None of its children [case] nodes contains this as an option, hence the [default] node will be evaluated,

and this results in setting the [.result] node's value to "Success!".

[default] cannot have a value, and all your [case] nodes must have a value, either a constant or an expression. However, any types can be used as values for your [case] nodes. And your [switch] node must at the very least have minimum one [case] node. The [default] node is optional though. You can mix and match different types as you see fit in your [case] nodes.

Comparisons

All comparison "operators" works the same way in Hyperlambda, in that they have an LHS and a RHS, implying respectively "Left Hand Side" and "Right Hand Side". However, since the "comparison operators" in Hyperlambda are slots themselves, this implies there is no "left" or "right" side in your comparison, implying the "left" parts of your comparison is the first argument, and the "right" side is the second argument. All comparison slots will consider types, which implies that boolean true will not be considered equal to the string value of "true", and the integer value of 5 is not the same as the decimal value of 5.0, etc.

You can provide the two arguments to these slots either as children nodes, where the first child node becomes the LHS part, and the second its RHS part - Or you can alternatively supply the LHS part as an expression leading to a value, at which point the only child argument assumed for your comparison becomes the RHS argument. Magic contains the following comparison slots out of the box.

[eq]

[eq] is the equality "operator" in Magic, and it requires two arguments, both of which will be evaluated as potential signals - And the result of evaluating [eq] will only be true if the values of these two arguments are exactly the same.

.src:int:5

eq

get-value:x:@.src

.:int:5

[neq]

[neq] is the not equal "operator" in Magic, and it requires two arguments, both of which will be evaluated as potential signals - And the result of evaluating [neq] will only be true if the values of these two arguments are not the same.

.src:int:5

neq

get-value:x:@.src

.:int:5

[lt]

[lt] will do a comparison between its two arguments, and only return true if its first argument is "less than" its seconds argument. Consider the following.

.src1:int:4

lt

get-value:x:@.src1

.:int:5

[lte]

[lte] will do a comparison between its two arguments, and only return true if its first argument is "less than or equal" to its seconds argument. Consider the following.

.src1:int:4

lte

get-value:x:@.src1

.:int:4

[mt]

[mt] will do a comparison between its two arguments, and only return true if its first argument is "more than" its seconds argument. Consider the following.

.src1:int:7

mt

get-value:x:@.src1

.:int:5

[mte]

[mte] will do a comparison between its two arguments, and only return true if its first argument is "more than or equal" to its seconds argument. Consider the following.

.src1:int:7

mte

get-value:x:@.src1

.:int:5

Commonalities for all comparison slots

All comparison slots can optionally be given an expression that will be assumed to be their LHS argument, or "Left Hand Side" argument, that if given will replace the first child argument. Below is an example for the [mte] slot, but all comparison slots works similarly.

.src1:int:7

mte:x:@.src1

.:int:5

In the above example the expression :x:@.src1 becomes the left hand side, while the child argument becomes the right hand

side of the comparison. To translate the above into how it might look like in a traditional programming language to

give you an idea of its structure please consider the following.

src1 >= 5

Due to that the [if] slot, the [else-if] slot, and the [while] slot can optionally be given slot invocations themselves as their conditions, and all comparison slots are slots - You can inject comparison slot invocations inside of for instance your [if] invocations, serving as the slot invocation declaring the condition for your [if]. Consider the following to understand this.

.result

.arg1:foo

if

eq:x:@.arg1

.:foo

.lambda

set-value:x:@.result

.:Yup!

The above is the equivalent of the following in a more traditional programming language.

string result;

var arg1 = "foo";

if (arg1 == "foo")

{

result = "Yup!";

}

Boolean logical conditions

[and]

[and] requires two or more arguments, and will only evaluate to true, if all of its arguments evaluates to true. Consider the following.

// Evaluates to false.

and

.:bool:true

.:bool:false

// Evaluates to true.

and

.:bool:true

.:bool:true

Notice, [and] will short circuit itself if it reaches a condition that does not evaluate to true, implying none of its conditions afterwards will be considered, since the [and] as a whole evaluates to false. [and] will also evaluate its arguments before checking if they evaluate to true, allowing you to use it as a part of richer comparison trees, such as the following illustrates.

.s1:bool:true

.s2:bool:true

.res

if

and

get-value:x:@.s1

get-value:x:@.s2

.lambda

set-value:x:@.res

.:OK

[or]

[or] is similar to [and], except it will evaluate to true if any of its arguments evaluates to true, such as the following illustrates. [or] will also evaluate its arguments, allowing you to use it as a part of richer comparison trees, the same way [and] allows you to. Below is a simple example.

// Evaluates to false.

or

.:bool:false

.:bool:false

// Evaluates to true.

or

.:bool:false

.:bool:true

[or] will also short circuit itself if it reaches a condition that evaluates to true, implying none of its conditions afterwards will be considered, since the [or] as a whole evaluates to true if any of its arguments evaluates to true.

[not]

[not] expects exactly one argument, and will negate its boolean value, whatever it is, such as the following illustrates.

not

.:bool:true

not

.:bool:false

[not] will also evaluate its argument, allowing you to use it in richer comparison trees, the same you could do with both [or] and [and]. Below is an example combining these slots together to create more complex types of logical comparisons.

.foo1:bar

.foo2:bool:false

.foo3:bool:true

.result

if

and

eq:x:@.foo1

.:bar

or

get-value:x:@.foo2

get-value:x:@.foo3

.lambda

set-value:x:@.result

.:Yup!

Notice you can actually follow the path the Hyperlambda executor took during execution of your code if you use the "Eval" menu item, since the result it produces for the above code will resemble the following.

.foo1:bar

.foo2:bool:false

.foo3:bool:true

.result:Yup!

if:bool:true

and:bool:true

eq:bool:true

.:bar

or:bool:true

get-value:bool:false

get-value:bool:true

.lambda

set-value:x:@.result

.:Yup!

In the above code we can see that the first child of our above [or] node evaluates to false, but since the

second child of our [or] node evaluates to true, the [or] as a whole evaluates to true. If you change

its [.foo2] data node to boolean true, you will see that your second child of [or] never even is

considered, since your [or] invocation is "short circuiting". You can nest as many [or] and [and]

invocations as you wish, creating any amount of complexity in your Hyperlambda.

Modifying your graph

Since there are no explicit variables in Hyperlambda, yet all nodes potentially might change, this requires the ability to change your nodes as you execute your Hyperlambda. Magic provides many slots to achieve this, both to change the names, values, and types of your nodes - In addition to adding a range of nodes into some other node, and/or remove nodes from the children collection of your nodes.

[add]

This slot allows you to dynamically add nodes into a destination node. Its primary argument is the destination, and it assumes that each children is a collection of nodes it should append to the destination node's children collection. The reasons for this additional level of indirection, is because the [add] slot might have children that are by themselves slot invocations, which it will evaluate before it starts adding the children nodes of these arguments to its destination node's children collection. Below is an example.

.dest

add:x:@.dest

.

foo1:howdy

foo2:world

.

bar1:hello

bar2:world

Notice how all the 4 nodes above (foo1, foo2, bar1, bar2) are appended into the [.dest] node's children collection. This construct allows you to evaluate slots and add the result of your slot invocations into the destination, such as the following illustrates.

.src

foo1:foo

foo2:bar

.dest

add:x:@.dest

get-nodes:x:@.src/*

[add] can also take an expression leading to multiple destinations as its main argument, allowing you to add a copy of your source nodes into multiple destination node collections simultaneously with one invocation. [add] can also be given multiple "source" node invocations. In the following example we illustrate both of these constructs at the same time.

.dest

.dest

.src1

foo1:bar1

.src2

foo2:bar2

add:x:../*/.dest

get-nodes:x:@.src1/*

get-nodes:x:@.src2/*

Notice how both of our [.dest] nodes above ends up having both the [foo1] and the [foo2] nodes in its children collection after executing the above Hyperlambda.

[insert-before]

This slot works the exact same way as the [add] node, except it will insert the nodes before the node(s) referenced in its main/destination argument.

.foo

foo1

foo2

insert-before:x:@.foo/*/foo1

.

inserted

[insert-after]

This slot works the exact same way as the [add] and [insert-before] slots, except it will insert the nodes after the node(s) referenced in its main/destination argument.

.foo

foo1

foo2

insert-after:x:@.foo/*/foo1

.

inserted

[remove-nodes]

This slot will remove all nodes its expression is pointing to.

.data

foo1

foo2

foo3

remove-nodes:x:@.data/*/foo2

[set-value]

Changes the value of all nodes referenced as its main expression to whatever its single source happens to be. Notice, when you invoke a slot that tries to change the value, name, or the node itself of some expression, and you supply a source expression to your invocation - Then the result of the source expression cannot return more than one result. The destination expression however can modify multiple nodes simultaneously.

.foo

.foo

set-value:x:../*/.foo

.:SUCCESS

[set-name]

Changes the name of all nodes referenced as its main expression to whatever its single source happens to be.

.foo

old-name

set-name:x:@.foo/*

.:new-name

The [set-name] invocation can also be given multiple destinations, but only one source.

[unwrap]

This slot is useful if you want to invoke another slot, but before you do, you want to evaluate some expressions inside of some argument to your slot. Imagine the following.

.src:Hello World

unwrap:x:+

.dest:x:@.src

In the above example, before the [.dest] node is reached by the Hyperlambda instruction pointer, the value of the [.dest] node will have been "unwrapped" (evaluated), and its value will be "Hello World". This slot becomes very handy when you invoke lambda objects with expressions, since it allows you to "forward evaluate" said expressions inside your lambda object, before the lambda object is actually executed. It's also useful when you have expressions inside for instance a [return] slot, and you want to return the value the expression evaluates to, and not the expression itself.

Source slots

In addition to the above slots allowing you to change your graph objects as they are executed, Hyperlambda also contains a whole range of slots that allows you to retrieve parts of your lambda objects during execution.

[get-value]

Returns the value of the node its expression is pointing to.

.data:Hello World

get-value:x:-

[get-name]

Returns the name of the node referenced in its expression.

.foo

get-name:x:-

[get-count]

This slot returns the number of nodes its expression is pointing to.

.data

foo1

foo2

get-count:x:@.data/*

[get-nodes]

Returns the nodes its expression is referencing.

.data

foo1

foo2

get-nodes:x:-/*

[exists]

[exists] will evaluate to true if its specified expression yields one or more results. If not, it will return false.

.src1

foo

.src2

exists:x:@.src1/*

exists:x:@.src2/*

[reference]

This slot will evaluate its expression, and add the entire node the expression is pointing to, as a referenced node into its value. This allows you to pass a node into a slot by reference, and have that slot modify the node itself, or its children. This might sometimes be useful to have slots modify some original graph object, or parts of a graph - Or get access to iterate over parts of your graph object's children.

.foo

reference:x:@.foo

set-value:x:-/#

.:Yup!

You can think of this slot as the singular version of [get-nodes], except instead of returning multiple nodes, it assumes its expression only points to a single node, and instead of returning a copy of the node, it returns the actual node by reference.

Notice - The /# iterator above, will enter into the node referenced as a value of its current

result - Implying it allows you to deeply traverse nodes passed in as references. This is sometimes

useful in combination with referenced nodes, passed in as values of other nodes. You should as a general

rule of thumb be careful with the [reference] slot, since it results in side effects for the caller if

it passes nodes by reference into some slot. Such side effects are as a general rule of thumb considered a bad thing,

since they result in unpredictable results. In theory passing in a node by reference to some slot, might change

the logic of the calling function, resulting in changing the code that is being executed, which obviously

makes the code literally impossible to understand. Hence, be careful with the [reference] slot!

[get-first-value]

Returns the first non-null value resulting from evaluating its expression, and/or its children nodes.

.data1

foo1:bar1

foo2:bar2

.data2:bar3

get-first-value:x:@.data1/*

get-value:x:@.data2

This node returns only the first non-null value resulting from evaluating its expression, and/or its children nodes. This is useful when you for instance have arguments to some lambda object, but want to apply default values if the argument is not specified - And or want to have guarantees of that only a single value is returned.

[get-context]

This slot returns a context stack object, which is an object added to the stack using [context]. Below is an example of usage.

.result

context:foo

value:bar

.lambda

set-value:x:@.result

get-context:foo

Notice how [get-context] inside your above [.lambda] invocation is able to retrieve the context object named "foo", having the value of "bar". See the [context] slot further down in this document for details about how this works.

Exceptions

Exceptions in Hyperlambda are similar to exceptions in traditional programming languages, and are basically a mechanism to raise errors in such a way that the stack is completely rewinded, to the point in your code where you want to handle error conditions. This allows you to "ignore" errors occurring in all places, except a single point in your code, from where you want to handle said exceptions.

[try]

This slot allows you to create a try/catch/finally block in Hyperlambda, from where exceptions are caught, and optionally handled in a [.catch] lambda, and/or a [.finally] lambda.

try

throw:Whatever

.catch

log.info:ERROR HAPPENED!! 42, 42, 42!

.finally

log.info:Yup, we are finally there!

Semantically this works the exact same way as try/catch/finally in other programming languages, such as C# for instance, in that an exception thrown inside of a try/catch block will always end up inside of its [.catch] block - And regardless of whether or not an exception is thrown, the [.finally] block will always execute, allowing you to some extend create deterministic execution of Hyperlambda code, which has a guarantee of executing, regardless of whether or not an exception is thrown or not.

[throw]

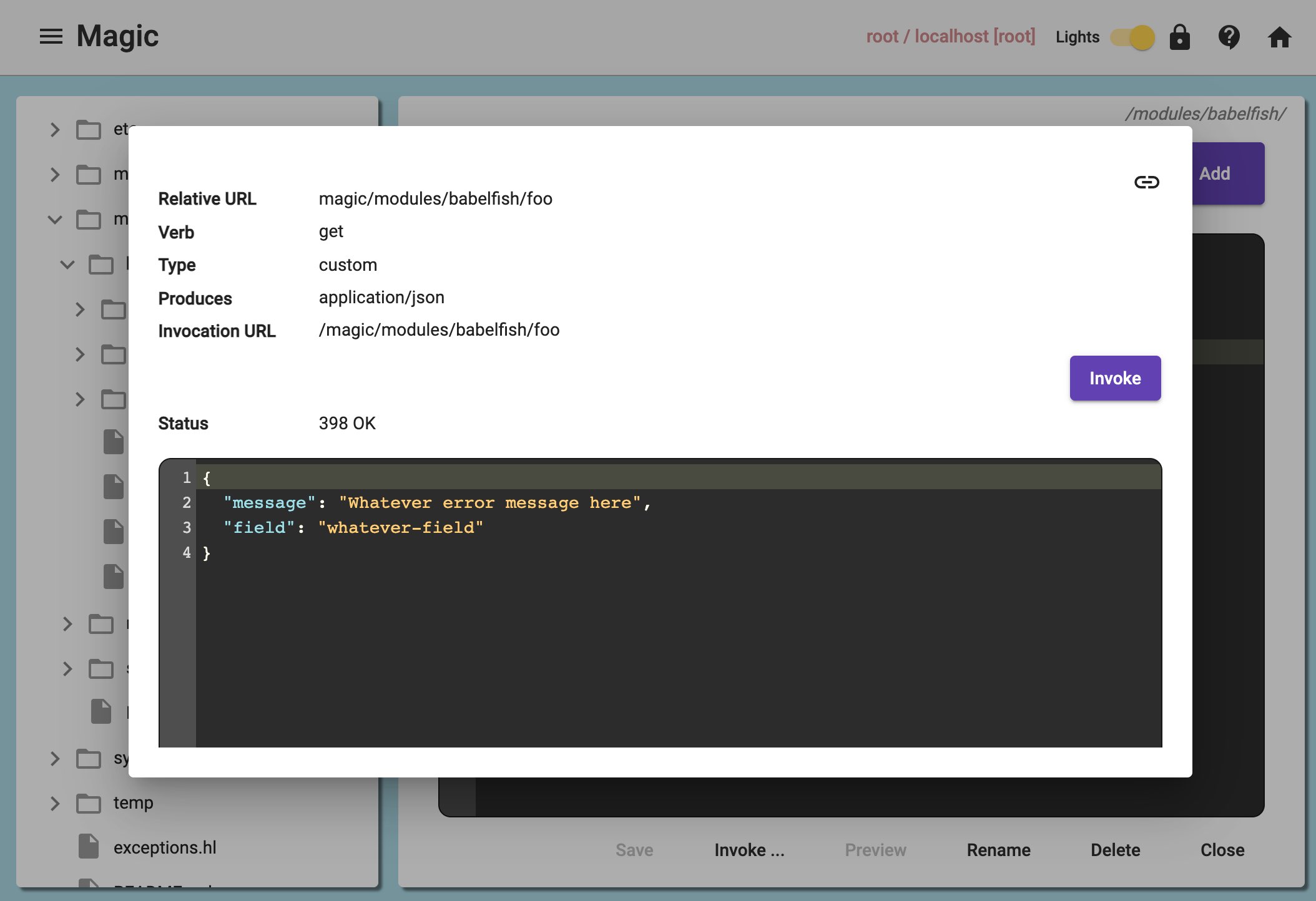

This slot simply throws an exception, with the exception message taken from its value. See the [try] slot above for an example. Notice, you can make the exception propagate to the client by adding a [public] parameter, and set its value to boolean "true" - At which point the exception will be returned to the client, even in release builds, if no [.catch] block handles it before it propagates to the client - Otherwise the exception will only be visible in debug builds, and never returned to the client. You can also modify the [status] HTTP return value that's returned to the client, to become e.g. 404, indicating "not found", etc. In addition you can pass in a [field] which will be serialised back to the client if specified to help the client to semantically figure out which field that triggered the exception. Below is an example of all of the above.

throw:Whatever error message here

status:398

public:true

field:whatever-field

If you create an endpoint using for instance "Hyper IDE", and throw the above exception, you can see how this propagates to the client without the exception handler. Below is a screenshot of how this will end up looking from the client's point of view.

Loops

Loops in programming languages implies doing something x number of times, where x is any number. Hyperlambda provides two basic slots for looping; [for-each] and [while].

[for-each]

[for-each] iterates through each node being the result of an expression, and evaluates its lambda object, passing in the currently iterated node as a [.dp] argument, containing the node currently iterated by reference.

.data

foo1

foo2

for-each:x:-/*

set-value:x:@.dp/#

.:hello

See the documentation for the [reference] slot to understand how reference nodes works.

[while]

Semantically similar to [if], but instead of evaluating its lambda object once, will iterate it for as long as the condition evaluates to true. Requires exactly two arguments, the same way [if] does.

.no:int:0

.res

while

lt

get-value:x:@.no

.:int:5

.lambda

add:x:@.res

.

foo

math.increment:x:@.no

The above Hyperlambda snippet basically implies the following if we are to translate it into plain English; "Set .no to 0, then loop while .no is less than 5, where the loop adds a node into .res, before it increments .no by 1".

Miscellaneous slots

These are slots that doesn't belong to one specific group of slots, but are still useful enough in general to have implementations in Hyperlambda.

[types]

This slot returns all Hyperlambda types your current installation supports.

types

[type]

This slot return the Hyperlambda type name of some value.

.foo:int:57

type:x:-

After invoking the above, the value of [type] will be int.

[convert]

This slot converts the value of an expression from its original type, to whatever [type] declaration you supply as its argument.

.foo:57

convert:x:-

type:int

Notice - You can also base64 encode and decode byte[] with this slot, by passing in "base64" or

"from-base64" as your [type] argument. The value of the object you want to convert must obviously support

conversion to the specified type, and will throw an exception if no conversion is possible, such as if you

for instance try to convert the string of "foo-bar" to an integer.

[format]

This slot converts some expression or value according to some specified String.Format pattern.

The following code will string format the number 57 to make sure it's prefixed with leading zeros, always ending

up having at least 5 digits. See .Net String.Format method for which patterns you can use. The culture used will

be the invariant one, unless you explicitly override the culture with a [culture] argument.

.foo:int:57

format:x:-

pattern:"{0:00000}"

To override the [culture] argument used you can use something such as follows.

.foo:decimal:57

format:x:-

pattern:"{0:0.00}"

culture:nb-NO

Since the above is using Norwegian Bokmal as its [culture] argument, it will return the result with a ,

as a decimal separator instead of the default which is .. You can use the same [pattern] values for

this slot as you can use in C# and .Net. To see an extensive list of for instance the formatting patterns you

can use for a date and time object, you can browse the Microsoft documentation

related to this. If you don't supply a [culture] argument the invariant culture will be used.

[vocabulary]

Returns the name of every static slot in your system, optionally passing in a string, or an expression leading to a string, which is a filtering condition, where the slot must start with the filter specified to be considered a part of the end result.

// Returns ALL slots in your system.

vocabulary

// Returns only slots starting with [io.file]

vocabulary:io.file

[whitelist]

This slot temporarily within the given scope changes the available slots, allowing you to declare a block of lambda, where only a sub-set of your vocabulary is available for some piece of code to invoke. This allows you to relatively securely allow some partially untrusted source to pass in a piece of Hyperlambda, for then to allow it to evaluate its own Hyperlambda. The slot takes two arguments.

- [vocabulary] - Whitelisted slots

- [.lambda] - Lambda object to evaluate for the given scope

.result

whitelist

vocabulary

set-value

return

.lambda

// Inside of this [.lambda] object, we can only invoke [set-value], and no other slots!

set-value:x:@.result

.:foo

// Notice, the next line will throw an exception if you remove its "." character,

// because [add] is not whitelisted in our above [vocabulary] declaration!

.add:x:@.result

.

foo:bar

return

result:success

For security reasons the [whitelist] invocation's [.lambda] object is immutable, and the caller cannot access nodes outside of the [.lambda] object itself, which prohibits the caller to modify, and/or read nodes from outside of its [whitelist] invocation. In addition a [whitelist] invocation creates its own result stack object, allowing the [whitelist] invocation to return values and nodes to the caller using for instance the [return] slot. If you execute the above Hyperlambda you can see how this semantically works by realizing how the above [.result] node never has its value actually changed, because our invocation to [set-value] inside our whitelist invocation yields a "null node-set result". Hence, semantically the [whitelist] slot works the same way signaling a dynamic slot works in Hyperlambda, in that the invocation treats its [.lambda] object as if it was a dynamic slot, isolating it from the rest of our code, allowing the lambda object to return values and nodes to the caller.

[context]

This slot allows you to add an object unto the stack, such that it can later be retrieved with the [get-context] slot. Below is an example.

.result

context:foo

value:bar

.lambda

set-value:x:@.result

get-context:foo

The slot requires a name as the value of its slot invocation node, a [value] as the value you want to put onto the stack, and a [.lambda] object being the lambda where the stack object exists, and can be retrieved using [get-context]. This is quite useful if you have some piece of data that needs to be accessible through the entirety of the execution of some Hyperlambda snippet, implying also for slots you invoke, where you don't want to pass in the data as an argument to the slot itself. Imagine the following to understand how this works.

slots.create:bar

get-context:foo

return:x:-

context:foo

value:Context value

.lambda

signal:bar

If you execute the above Hyperlambda you will notice how the slot called [bar] actually has access to the context value called "foo", and can retrieve this. This feature allows you to declare and create "long lasting arguments" that are accessible from within the entirety of a piece of Hyperlambda, including each slot it invokes, and/or Hyperlambda files it executes.

[apply]

This slot takes an expression in addition to a list of arguments, and "applies" the arguments unto the expression's result node set, allowing you to perform dynamic substitutions on lambda hierarchies such as the following illustrates.

.lambda

foo

arg1:{some_arg}

some-static-node:static-value

apply:x:-

some_arg:value of argument

After execution of the above Hyperlambda you will have a result resembling the following.

apply

foo

arg1:value of argument

some-static-node:static-value

Notice how the nodes from your template lambda object have been copied as children into your [apply]

node, while during this "copying process", the arguments you supplied to [apply] have been used

to perform substitutions on all nodes in your template lambda having a value of {xxx}, where xxx is

your argument name. In the above example for instance the arg1:{some_arg} template node had its value

replaced by the value of the [some_arg] node passed in as a parameter to [apply]. If the name of

the argument to [apply], matches the value of your template node wrapped inside curly braces - Then

the value of your argument to apply becomes the new value of your template node after substitution has

been performed.

Only node values starting out with { and ending with } will be substituted, and you are expected to provide

all arguments found in the template lambda object, or the invocation will fail, resulting in an exception. This

allows you to create "template lambda objects" that you dynamically transform into something else, without

really caring about its original structure, but rather only its set of dynamic substitution arguments. This

slot leaves all other nodes as is.

Basically, the way it works, is that it takes your expression, and recursively iterate each node below the

result of your expression, checks to see if the node's value is an argument such as e.g. {howdy} -

And if so, it substitutes the {howdy} parts with the value of the argument you are expected to supply to your

invocation having the name [howdy].

You can also reference the same argument multiple times in your template, in addition to create arguments that are lambda objects instead of simple values. Below is an example of both of these constructs.

.lambda

foo

foo1:{arg1}

foo2:{arg1}

foo3:{arg2}

apply:x:-

arg1:int:5

arg2

this:is

an:entire

lambda:object

used_as_an_argument:int:7

The above will result in the following.

apply

foo

foo1:int:5

foo2:int:5

foo3

this:is

an:entire

lambda:object

used_as_an_argument:int:7

Above you can also see how typing information is not lost, since the [foo1] and [foo2] nodes are both having integrer values of 5 after apply is done executing. At the same time you can see how the [foo3] node instead of having a simple value applied, actually ended up with a copy of all children passed in as [arg2]. You can also substitute names of nodes, such as the following illustrates.

.lambda

foo

{arg1}:value-is-preserved

apply:x:-

arg1:foo1

The above of course results in the following.

apply

foo

foo1:value-is-preserved

This is a fairly advanced slot, but it's the heart of the generator, allowing us to generate HTTP endpoints, starting out with some template file, which is dynamically changed, according to input arguments supplied during the crudification process. You can also combine transformations of names, values, and children in the same template nodes. The process is also recursive in nature, performing substitutions through the entire hierarchy of your template lambda.

Project website

The source code for this repository can be found at github.com/polterguy/magic.lambda, and you can provide feedback, provide bug reports, etc at the same place.

Quality gates

| Product | Versions Compatible and additional computed target framework versions. |

|---|---|

| .NET | net5.0 was computed. net5.0-windows was computed. net6.0 was computed. net6.0-android was computed. net6.0-ios was computed. net6.0-maccatalyst was computed. net6.0-macos was computed. net6.0-tvos was computed. net6.0-windows was computed. net7.0 was computed. net7.0-android was computed. net7.0-ios was computed. net7.0-maccatalyst was computed. net7.0-macos was computed. net7.0-tvos was computed. net7.0-windows was computed. net8.0 was computed. net8.0-android was computed. net8.0-browser was computed. net8.0-ios was computed. net8.0-maccatalyst was computed. net8.0-macos was computed. net8.0-tvos was computed. net8.0-windows was computed. |

| .NET Core | netcoreapp2.0 was computed. netcoreapp2.1 was computed. netcoreapp2.2 was computed. netcoreapp3.0 was computed. netcoreapp3.1 was computed. |

| .NET Standard | netstandard2.0 is compatible. netstandard2.1 was computed. |

| .NET Framework | net461 was computed. net462 was computed. net463 was computed. net47 was computed. net471 was computed. net472 was computed. net48 was computed. net481 was computed. |

| MonoAndroid | monoandroid was computed. |

| MonoMac | monomac was computed. |

| MonoTouch | monotouch was computed. |

| Tizen | tizen40 was computed. tizen60 was computed. |

| Xamarin.iOS | xamarinios was computed. |

| Xamarin.Mac | xamarinmac was computed. |

| Xamarin.TVOS | xamarintvos was computed. |

| Xamarin.WatchOS | xamarinwatchos was computed. |

-

.NETStandard 2.0

- magic.node.extensions (>= 11.0.0)

- magic.signals (>= 11.0.0)

NuGet packages (1)

Showing the top 1 NuGet packages that depend on magic.lambda:

| Package | Downloads |

|---|---|

|

magic.library

Helper project for Magic to wire up everything easily by simply adding one package, and invoking two simple methods. When using Magic, this is (probably) the only package you should actually add, since this package pulls in everything else you'll need automatically, and wires up everything sanely by default. To use package go to https://polterguy.github.io |

GitHub repositories

This package is not used by any popular GitHub repositories.

| Version | Downloads | Last updated |

|---|---|---|

| 17.1.7 | 434 | 1/12/2024 |

| 17.1.6 | 392 | 1/11/2024 |

| 17.1.5 | 440 | 1/5/2024 |

| 17.0.1 | 488 | 1/1/2024 |

| 17.0.0 | 713 | 12/14/2023 |

| 16.11.5 | 701 | 11/12/2023 |

| 16.9.0 | 737 | 10/9/2023 |

| 16.7.0 | 1,109 | 7/11/2023 |

| 16.4.1 | 914 | 7/2/2023 |

| 16.4.0 | 922 | 6/22/2023 |

| 16.3.1 | 834 | 6/7/2023 |

| 16.3.0 | 836 | 5/28/2023 |

| 16.1.9 | 1,149 | 4/30/2023 |

| 15.10.11 | 988 | 4/13/2023 |

| 15.9.1 | 1,111 | 3/26/2023 |

| 15.9.0 | 969 | 3/24/2023 |

| 15.8.2 | 1,011 | 3/20/2023 |

| 15.7.0 | 947 | 3/6/2023 |

| 15.5.0 | 2,119 | 1/28/2023 |

| 15.2.0 | 1,313 | 1/18/2023 |

| 15.1.0 | 1,661 | 12/28/2022 |

| 14.5.7 | 1,255 | 12/13/2022 |

| 14.5.5 | 1,324 | 12/6/2022 |

| 14.5.1 | 1,187 | 11/23/2022 |

| 14.5.0 | 1,121 | 11/18/2022 |

| 14.4.5 | 1,272 | 10/22/2022 |

| 14.4.1 | 1,284 | 10/22/2022 |

| 14.4.0 | 1,163 | 10/17/2022 |

| 14.3.9 | 1,171 | 10/13/2022 |

| 14.3.1 | 1,599 | 9/12/2022 |

| 14.3.0 | 1,178 | 9/10/2022 |

| 14.1.3 | 1,456 | 8/7/2022 |

| 14.1.2 | 1,187 | 8/7/2022 |

| 14.1.1 | 1,179 | 8/7/2022 |

| 14.0.14 | 1,228 | 7/26/2022 |

| 14.0.12 | 1,148 | 7/24/2022 |

| 14.0.11 | 1,158 | 7/23/2022 |

| 14.0.10 | 1,102 | 7/23/2022 |

| 14.0.9 | 1,141 | 7/23/2022 |

| 14.0.8 | 1,226 | 7/17/2022 |

| 14.0.5 | 1,342 | 7/11/2022 |

| 14.0.4 | 1,304 | 7/6/2022 |

| 14.0.3 | 1,223 | 7/2/2022 |

| 14.0.2 | 1,199 | 7/2/2022 |

| 14.0.0 | 1,371 | 6/25/2022 |

| 13.4.0 | 2,598 | 5/31/2022 |

| 13.3.4 | 1,908 | 5/9/2022 |

| 13.3.0 | 1,491 | 5/1/2022 |

| 13.2.0 | 1,702 | 4/21/2022 |

| 13.1.0 | 1,551 | 4/7/2022 |

| 13.0.0 | 1,210 | 4/5/2022 |

| 11.0.5 | 1,948 | 3/2/2022 |

| 11.0.4 | 1,261 | 2/22/2022 |

| 11.0.3 | 1,328 | 2/9/2022 |

| 11.0.2 | 1,316 | 2/6/2022 |

| 11.0.1 | 1,008 | 2/5/2022 |

| 11.0.0 | 1,297 | 2/5/2022 |

| 10.0.21 | 1,249 | 1/28/2022 |

| 10.0.20 | 1,238 | 1/27/2022 |

| 10.0.19 | 1,254 | 1/23/2022 |

| 10.0.18 | 1,206 | 1/17/2022 |

| 10.0.16 | 1,082 | 1/14/2022 |

| 10.0.15 | 1,294 | 12/31/2021 |

| 10.0.14 | 1,125 | 12/28/2021 |

| 10.0.7 | 2,022 | 12/22/2021 |

| 10.0.5 | 1,268 | 12/18/2021 |

| 9.9.9 | 2,175 | 11/29/2021 |

| 9.9.3 | 1,776 | 11/9/2021 |

| 9.9.2 | 1,518 | 11/4/2021 |

| 9.9.0 | 1,828 | 10/30/2021 |

| 9.8.9 | 1,626 | 10/29/2021 |

| 9.8.7 | 1,584 | 10/27/2021 |

| 9.8.6 | 1,568 | 10/27/2021 |

| 9.8.5 | 1,595 | 10/26/2021 |

| 9.8.0 | 2,474 | 10/20/2021 |

| 9.7.9 | 1,515 | 10/19/2021 |

| 9.7.5 | 2,630 | 10/14/2021 |

| 9.7.3 | 884 | 10/14/2021 |

| 9.7.1 | 1,060 | 10/14/2021 |

| 9.7.0 | 1,628 | 10/9/2021 |

| 9.6.6 | 1,717 | 8/14/2021 |

| 9.2.0 | 7,545 | 5/26/2021 |

| 9.1.4 | 2,361 | 4/21/2021 |

| 9.1.0 | 1,979 | 4/14/2021 |

| 9.0.0 | 1,790 | 4/5/2021 |

| 8.9.9 | 2,038 | 3/30/2021 |

| 8.9.3 | 2,452 | 3/19/2021 |

| 8.9.2 | 1,968 | 1/29/2021 |

| 8.9.1 | 2,033 | 1/24/2021 |

| 8.9.0 | 2,146 | 1/22/2021 |

| 8.6.9 | 3,884 | 11/8/2020 |

| 8.6.7 | 1,759 | 11/4/2020 |

| 8.6.6 | 2,015 | 11/2/2020 |

| 8.6.3 | 1,762 | 11/1/2020 |

| 8.6.2 | 2,493 | 10/30/2020 |

| 8.6.0 | 2,753 | 10/28/2020 |

| 8.5.0 | 2,835 | 10/23/2020 |

| 8.4.3 | 3,528 | 10/17/2020 |

| 8.4.2 | 1,800 | 10/16/2020 |

| 8.4.1 | 1,706 | 10/16/2020 |

| 8.4.0 | 2,739 | 10/13/2020 |

| 8.3.1 | 3,444 | 10/5/2020 |

| 8.3.0 | 2,055 | 10/3/2020 |

| 8.2.2 | 2,801 | 9/26/2020 |

| 8.2.1 | 2,065 | 9/25/2020 |

| 8.2.0 | 2,054 | 9/25/2020 |

| 8.1.18 | 1,846 | 9/23/2020 |

| 8.1.17 | 6,842 | 9/13/2020 |

| 8.1.16 | 1,380 | 9/13/2020 |

| 8.1.15 | 1,986 | 9/12/2020 |

| 8.1.11 | 3,915 | 9/11/2020 |

| 8.1.10 | 1,584 | 9/6/2020 |

| 8.1.9 | 3,129 | 9/3/2020 |

| 8.1.8 | 2,161 | 9/2/2020 |

| 8.1.7 | 1,908 | 8/28/2020 |

| 8.1.4 | 1,977 | 8/25/2020 |

| 8.1.3 | 1,830 | 8/18/2020 |

| 8.1.2 | 1,743 | 8/16/2020 |

| 8.1.1 | 1,732 | 8/15/2020 |

| 8.1.0 | 1,140 | 8/15/2020 |

| 8.0.1 | 3,159 | 8/7/2020 |

| 8.0.0 | 1,770 | 8/7/2020 |

| 7.0.1 | 1,835 | 6/28/2020 |

| 7.0.0 | 1,739 | 6/28/2020 |

| 5.0.1 | 1,725 | 5/31/2020 |

| 5.0.0 | 7,333 | 2/25/2020 |

| 4.0.4 | 8,263 | 1/27/2020 |

| 4.0.3 | 1,748 | 1/27/2020 |

| 4.0.2 | 1,930 | 1/16/2020 |

| 4.0.1 | 1,893 | 1/11/2020 |

| 4.0.0 | 1,855 | 1/5/2020 |

| 3.1.1 | 2,561 | 12/12/2019 |

| 3.1.0 | 5,398 | 11/10/2019 |

| 3.0.0 | 4,410 | 10/23/2019 |

| 2.0.2 | 2,289 | 10/21/2019 |

| 2.0.1 | 7,622 | 10/15/2019 |

| 2.0.0 | 2,127 | 10/13/2019 |

| 1.2.2 | 1,838 | 10/11/2019 |

| 1.2.1 | 1,874 | 10/10/2019 |

| 1.2.0 | 1,100 | 10/10/2019 |

| 1.1.9 | 1,102 | 10/9/2019 |

| 1.1.8 | 1,048 | 10/9/2019 |

| 1.1.7 | 1,031 | 10/7/2019 |

| 1.1.6 | 1,101 | 10/6/2019 |

| 1.1.5 | 1,068 | 10/6/2019 |

| 1.1.3 | 5,121 | 10/6/2019 |

| 1.1.0 | 4,617 | 10/5/2019 |

| 1.0.1 | 1,468 | 9/26/2019 |

| 1.0.0 | 1,082 | 9/26/2019 |